4 Lists

Before you begin to write a program we have a data type called lists and its cousin tuple. ## List Data Type a list is a value that contains multiple values in an ordered sequence. Values inside that list are also considered as items. Imagine you have a magic box called a “list” In this box, you can put many things, like toys, books, or candies. A list in programming is like that magic box, but it holds different pieces of information, not just toys.

In a list, you can store numbers, words, or a mix of both. For example, you can have a list of your favorite colors: ['red', 'blue', 'green']. Each color is like a special item in the box.

You can also tell the list to do things, like showing you all the colors or adding a new color. It helps you keep things organized, just like your magic box keeps your toys in order.

Here’s a simple example in Python:

favorite_colors = ['red', 'blue', 'green']

print("My favorite colors are:", favorite_colors)In this case, the list is ['red', 'blue', 'green'], and the program tells the computer to print those colors. Lists are like magical containers that make it easy to work with different pieces of information in a program.

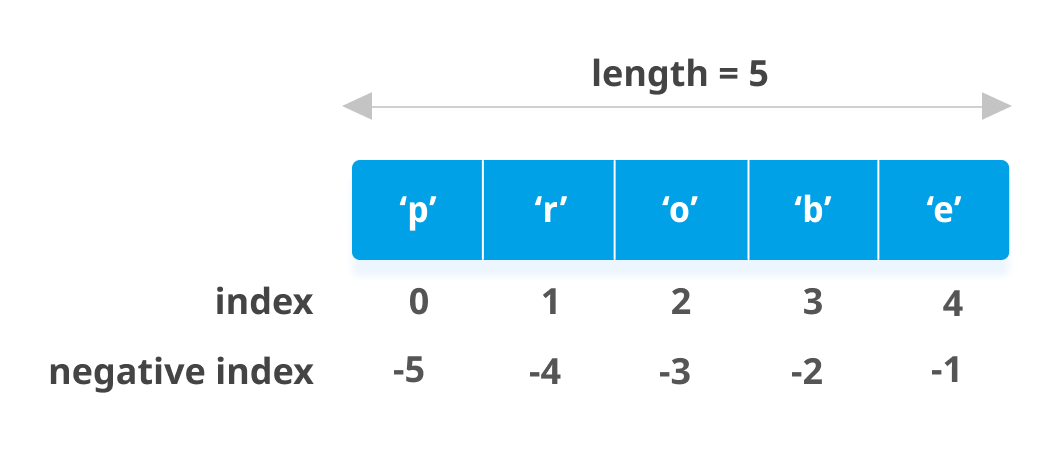

4.1 Getting Values in a List with Indexes

Say you have a list ['red', 'blue', 'green', 45, True] stored in a variable named colors. If we want to access elements from this list we have to access it by its index (index is like the address of that item on the memory). e.g. colors[0] would return red and so on. Since list indexing starts with 0 that’s why to access the 5th element of the list you have to give it 4 or len(list)-1 less than one of the total length of the list.

We can also use negative indexing to display the list in reverse order or to iterate on the list from backward.

For example, try the following in the interactive shell.

colors = ['blue','green','red','brown','white', 9124, True, False, 9.33]

colors = ['blue','green','red','brown','white', 9124, True, False, 9.33]

colors[0]

'blue'

1colors[-1]

9.33

colors[-2]

False

colors[-3]

True

colors[-4]

9124

colors[2]

'red'

colors[3]

'brown'

2colors[1:4]

['green', 'red', 'brown']

colors[0:4]

['blue', 'green', 'red', 'brown']- 1

-

Here, we are using the negative indexing to iterate from the back of the list and

colors[-1]will return the last element/item of the list. - 2

-

We can also use the slicing (a range of values in a list) in a list to specify the range to tell it where to start and where to stop.

colors[0:4]Here, you can see we tell Python to start from the index 0 and goes upto 4 (but 4 is not included because indexing starts from 0 that’s why it will stop on 3. if you start from 0 like (0, 1, 2, 3) == 4 elements.)

4.2 Nested List

Let’s create a Nested list in Python:

cars = ['toyota', 'mercedes', 'benz', ['tesla x', 'tesla y', 'tesla z']]

print(cars[0:2]) # Output: ['toyota', 'mercedes', 'benz']

1print(cars[3]) # Output: ['tesla x', 'tesla y', 'tesla z']

2print(cars[3][0]) # Output: 'tesla x'

3print(cars[3][0:2]) # Output: ['tesla x', 'tesla y']- 1

-

cars[3]will give the value on index 3 which is the nested list inside thecarslist. - 2

-

This

cars[3][0]expression tells Python to go on the third item on the listcarsthen on the third element fetch element on index0and return it. - 3

-

cars[3][0:2]expression tells Python to extract elements ranging from 0 up to 2 from the nested list withincars.

4.3 Changing Values of a List by Indexes

Normally, when we change the value of a variable we use the variable name and the corresponding value, But in the case of lists we use the index to change the value of a particular item. e.g. Let’s look at the following coding example:

cars = ['toyota', 'mercedes', 'benz', ['tesla x', 'tesla y', 'tesla z']]

cars[0] = 'Toyota Phoenix'

print(cars[0]) # value changed from 'toyota' to 'Toyota Phoenix'

# Changing the value using Negative indexing

cars[-1] = ['A', 'B', 'C', 'D'] # This replaces the list of Tesla car names

print(cars[-1])

# Print the whole list

print(cars)4.4 List Concatenation & Replication

To concatenate the list we can use the + operator and to make multiple copies we use the * operator just like the following:

# The multiplication operator will create 3 copies of the same list and will merge them

print([1, 2, 3, 4] * 3)

# Addition operator concatenates or chains together multiple lists into a single list.

print([1, 2, 3, 4] + [5, 6, 7, 8] + [9, 10, 11, 12, 13])4.5 Removing Values from Lists

The remove(), pop(), and del are three different methods in Python used for removing elements from a list, but they have distinct functionalities:

remove(value)Method:Usage:

list.remove(value)Functionality: Removes the first occurrence of the specified value from the list.

Example:

my_list = [10, 20, 30, 20, 40] my_list.remove(20) print(my_list) # Output: [10, 30, 20, 40]

pop(index)Method:Usage:

element = list.pop(index)Functionality: Removes and returns the element at the specified index. If no index is provided, it removes and returns the last element.

Example:

my_list = [10, 20, 30, 40] removed_element = my_list.pop(1) print(removed_element) # Output: 20 print(my_list) # Output: [10, 30, 40]

delStatement:- Usage:

del list[index]ordel list[start:end]ordel list - Functionality: Deletes the specified element(s) or the entire list.

- Examples:

Delete a specific element by index:

my_list = [10, 20, 30, 40] del my_list[1] print(my_list) # Output: [10, 30, 40]Delete a slice of the list:

my_list = [10, 20, 30, 40] del my_list[1:3] print(my_list) # Output: [10, 40]Delete the entire list:

my_list = [10, 20, 30, 40] del my_list # Raises an error if you try to access my_list after deletion

- Usage:

Key Points:

remove()is used when you know the value you want to remove.pop()is used when you want to remove an element by its index and optionally retrieve its value.delis a more general statement that can delete elements by index or slices, or even delete entire lists.

Choose the method that best fits your specific use case based on whether you need to remove by value, by index, or delete specific elements or slices.

4.6 Working with Lists

When you first begin writing programs it’s tedious to create many variables of the same type. For example to store my car collection:

# Long way to store multiple values in different variable names

Certainly! Here are nine different car model names:

car1 = "Toyota Camry"

car2 = "Ford Mustang"

car3 = "Honda Civic"

car4 = "BMW 3 Series"

car5 = "Chevrolet Corvette"

car6 = "Mercedes-Benz E-Class"

car7 = "Volkswagen Golf"

car8 = "Tesla Model S"

car9 = "Nissan Rogue"This turns out that this is a bad way to write code. (I also don’t own these cars, I swear, I just copied these names from the Internet)

Instead of using multiple repetitive variables, you can use a single variable that has list of values. For example, here’s a new and improved version of the above source code.

cars_collection = []

while True:

print('Enter the name of Car or Leave it empty to Quit:')

name = input()

if name == "":

break

else:

# list Concatenation

cars_collection = cars_collection + [name]

print('Collection: ',cars_collection)4.7 Iterate through Lists

In the previous lessons we have seen loops execute a block of code a certain number of times. For loop execute the code in the loop body for each item in the range. e.g.

for i in range(4):

print(i)

""" Output: 0

1

2

3

"""

# This is because Python looks at this range function as [0, 1, 2, 3] and retrieves an item at a time from the list.We will use the range function to iterate through the following list and will access values by its index:

cars_collection = ["Toyota Camry",

"Ford Mustang",

"Honda Civic",

"BMW 3 Series",

"Chevrolet Corvette",

"Mercedes-Benz E-Class",

"Volkswagen Golf",

"Tesla Model S",

"Nissan Rogue"]

# Assign the first value of the list to the 'car_name' variable and print it.

for car_name in cars_collection:

print(car_name)

# Accessing value by index, range() & len() function

for index in range(len(cars_collection)):

print(cars_collection[index])4.8 in and not in Operators

We can determine whether a value is present in a list or not by using in & not in operators. e.g. Enter the following into the interactive shell:

# Output: True

'salih' in ['sadiq','safi','salih','qaisar','ikram']

animals = ['cat', 'dog', 'bird', 'cow']

'cat' in animals # Output: True

'elephant' in animals # Output: False4.9 Multiple Assignment using Lists

Toyota = ['20 miles', '2016', '2024', 'Red']

mileage, model, year, color = toyota[0], toyota[1], toyota[2], toyota[3]

print(mileage)

print(model)

print(year)

print(color)You can also assign values to variables like below:

Toyota = ['20 miles', '2016', '2024', 'Red']

mileage, model, year, color = Toyota

print(mileage)

print(model)

print(year)

print(color)4.10 Using enumerate() function with Lists

The enumerate() function is useful if you want both index & value. Instead of using range(len(list name)) let’s do the same with enumerate().

cars_collection = ["Toyota Camry",

"Ford Mustang",

"Honda Civic",

"BMW 3 Series",

"Chevrolet Corvette",

"Mercedes-Benz E-Class",

"Volkswagen Golf",

"Tesla Model S",

"Nissan Rogue"]

for index, value in enumerate(cars_collection):

print(f'Index is: {index}\nValue is: {value}')

Starting Index from a Specific Value:

my_list = ['apple', 'banana', 'orange']

for index, value in enumerate(my_list, start=1):

print(f"Index: {index}, Value: {value}")Using Random module with Lists

The random module in Python can be used to perform various operations with lists. Here are a few examples:

Shuffling a List:

import random my_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] random.shuffle(my_list) print("Shuffled List:", my_list)Selecting a Random Element from a List:

import random fruits = ['apple', 'banana', 'orange', 'grape', 'kiwi'] random_fruit = random.choice(fruits) print("Random Fruit:", random_fruit)Random Sampling from a List:

import random numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] random_sample = random.sample(numbers, k=3) print("Random Sample:", random_sample)Generating Random Numbers within a Range:

import random random_number = random.randint(1, 100) print("Random Number between 1 and 100:", random_number)Randomizing List Order for a Specific Task:

import random tasks = ['Task A', 'Task B', 'Task C', 'Task D'] random.shuffle(tasks) print("Randomized Order for Task Execution:", tasks)

These are just a few examples, and the random module provides more functions for working with randomness in Python. Depending on your specific use case, you can choose the appropriate function from the random module to achieve the desired behavior with lists.

4.11 In-Place Operators or Compound Assignment Operators:

In Python, augmented assignment operators are shorthand syntax for performing an operation and assigning the result to the same variable. They combine an operation (like addition or multiplication) with the assignment. Here are some examples:

Addition:

+=x = 5 x += 3 # Equivalent to x = x + 3 print(x) # Output: 8Subtraction:

-=y = 10 y -= 4 # Equivalent to y = y - 4 print(y) # Output: 6Multiplication:

*=z = 3 z *= 2 # Equivalent to z = z * 2 print(z) # Output: 6Division:

/=a = 15 a /= 3 # Equivalent to a = a / 3 print(a) # Output: 5.0Modulus:

%=b = 17 b %= 5 # Equivalent to b = b % 5 print(b) # Output: 2Exponentiation:

**=c = 2 c **= 3 # Equivalent to c = c ** 3 print(c) # Output: 8Floor Division:

//=d = 25 d //= 4 # Equivalent to d = d // 4 print(d) # Output: 6

These operators are concise ways to update the value of a variable based on its current value and the result of an operation. They can be useful for making code more readable and efficient.

4.12 insert() & append() methods of List

Let’s keep it simple:

append()method:- What it does: Adds something to the end of a list.

- Example: If you have a list of fruits and you want to add a new fruit to the end, you use

append().

insert()method:- What it does: Adds something to a specific position in a list.

- Example: If you have a list of friends and you want to add a new friend at a particular spot, you use

insert().

So, append() adds to the end, and insert() adds at a specific place. Easy, right?

# Using append() to add to the end of a list

fruits = ['apple', 'banana', 'orange']

fruits.append('grape')

# Now, fruits is ['apple', 'banana', 'orange', 'grape']

# Using insert() to add at a specific position in a list

friends = ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie']

friends.insert(1, 'David')

# Now, friends is ['Alice', 'David', 'Bob', 'Charlie']4.13 Sorting value of list using sort() Method:

Values inside the list can be sorted with sort() method:

number = [1,5,3,2,7,4,3]

# Sort it in ascending order

number.sort()

print('Descending order: ',number)

# Sort it in descending order by passing `reverse` parameter

number.sort(reverse=True)

print('Ascending order: ',number)

# You can also sort list contain strings in alphabetical order

# You cannot sort list contain both string & number

# sort() uses 'ASCIIbetical order' rather than actual alphabetical order for sorting strings which means uppercase letters comes before lowercase letters.

my_list = ['apple','Apple', 'banana', 'Banana', 'orange',

'grape', 'kiwi', 'melon', 'peach', 'pear', 'strawberry', 'blueberry']

my_list.sort()

print(my_list)4.14 Reversing the Values of List

To reverse the order of a list you can call reverse() method on the list. e.g.

count = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

count.reverse()

print(count)Some time we want to organize our long line of code and to make it look pretty and readable. So, we use line continuation character at the end. This tells python that line is continues and it don’t end here. For example, look at the following code:

long_text = "This is a very long text that \

continues on the next line using the continuation character."

print(long_text)

# Continuation on lists

colors = ['red', 'green', 'blue', \

'yellow', 'orange', 'purple']

print(colors)

# Continuation on numbers

equation = 3 + \

5 * \

2

print(equation)4.15 String & Lists Similarities

In Python, strings and lists share some similarities:

- Ordered Sequence:

- Both strings and lists are ordered sequences, meaning the order in which elements appear is maintained.

- Indexing:

- You can access individual elements in both strings and lists using indexing. For example,

my_string[0]ormy_list[0]refers to the first element.

- You can access individual elements in both strings and lists using indexing. For example,

- Slicing:

- Both support slicing to extract a portion of the sequence. For instance,

my_string[1:4]ormy_list[1:4]extracts elements from index 1 to 3.

- Both support slicing to extract a portion of the sequence. For instance,

- Iterability:

- Both can be iterated using loops. You can use a

forloop to go through each character in a string or each element in a list.

- Both can be iterated using loops. You can use a

- Concatenation:

- You can concatenate strings using the

+operator, and you can concatenate lists using the+operator as well.

- You can concatenate strings using the

- Inclusion:

- Both can use the

inoperator to check if a specific element is present in the sequence.

- Both can use the

Here’s a quick example showcasing these similarities:

# Strings

my_string = "Hello, World!"

print(my_string[0]) # Output: H

print(my_string[7:12]) # Output: World

print('W' in my_string) # Output: True

# Lists

my_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

print(my_list[2]) # Output: 3

print(my_list[1:4]) # Output: [2, 3, 4]

print(3 in my_list) # Output: TrueDespite these similarities, it’s crucial to note that strings are immutable (you can’t change individual characters once the string is created), while lists are mutable (you can modify, add, or remove elements).

4.16 Tuple cousin of Lists

Tuples are identical to lists except it create with parenthesis () rather than curly braces [] like lists. Another distinction between list & tuple is that tuple is immutable (can’t change its values) like strings. If you want to create a tuple with a single value then type a single comma after the value. This comma is what lets Python know this is a tuple value. If you don’t place trailing comma after the value Python will think of it as a regular string:

Type the following into editor & see its types:

not_tup = ('hours')

print(type(tup))

tup = ('hours',)

print(type(tup))

my_list = ['hours']

print(type(my_list))Now, let’s create some tuples and try to tweak it a little bit and apply some of the list operations on it:

my_tuple = ('apple', 5, 3.14, 'banana', 7, 2.718)

# looping through tuple using slicing

print(my_tuple[1:3])

# Accessing value the way we access of list

1print(my_tuple[0])

# Changing the value of tuple (Remember tuple are Immutable)

2my_tuple[0] = 'Apple'- 1

- We can access tuple value like the way we access of lists.

- 2

-

This will cause error

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignmentbecause tuple values can’t be changed

4.17 Converting Types with list() & tuple() functions

The list() and tuple() functions in Python are used for converting between different sequence types. Here are some common use cases for these functions:

4.17.1 list() functions:

Convert String to List of Words:

my_string = "Hello, how are you?" word_list = list(my_string.split()) print(word_list)Convert Range to List:

number_range = range(1, 6) number_list = list(number_range) print(number_list)Clone Another List:

original_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] new_list = list(original_list)Convert Tuple to List:

# Converting tuple to list my_tuple = (10, 20, 30, 40, 50) my_list = list(my_tuple) print(my_list)

4.17.2 tuple() functions:

Convert List to Tuple:

my_list = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50] my_tuple = tuple(my_list) print(my_tuple)Convert String to Tuple of Characters:

my_string = "Python" char_tuple = tuple(my_string) print(char_tuple)Create a Tuple from Values:

values_tuple = tuple(1, 2, 3, 4, 5) print(values_tuple)These functions are versatile and can be used in various scenarios where you need to convert one sequence type to another.

4.18 Reference to Variables

Variables in Python act as references to objects (values) in memory. For example, when you do x = 10, x is a reference to the memory location where the value 10 is stored. Let’s look at the following code block:

# Creating references

a = 5 # 'a' is a reference to the value 5

b = [1, 2, 3] # 'b' is a reference to a list [1, 2, 3]

# Modifying through references

a = a + 1 # Creates a new object (6) and updates 'a' to reference it

b.append(4) # Modifies the list object directly

# Passing references to a function

def modify_list(lst):

lst.append(5)

modify_list(b) # 'b' is passed by reference, and the list is modified

# Changing reference

c = b # 'c' now references the same list as 'b'In simple words, reference means when you create variable var1 = data variable (var1) point to the address of value data on computer memory. For example in the following code you can find the address of a variable using id() function.

# Creating different names variable with same value

1var1 = 'data'

var2 = 'data'

var3 = 'data'

# Find memory address using id() method

print(id(var1))

print(id(var2))

print(id(var3))

# Create variable with different value

2var4 = 'data1'

var5 = 'data2'

print(id(var4))

print(id(var5))- 1

- As you can see these three variable have same value so their value won’t create separate memory address rather all of them will point to the same memory address.

- 2

-

var4&var5have different values so each variable will create their own memory address.

computers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

laptop = computers

mobile = computers

# Below all will return the same memory address because all of the variable have same value. So, all of them would point to the memory address of [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] instead of creating identical copy of it.

print(f'Address 1: {id(computers)}\nAddress 2: {id(laptop)}\nAddress 3: {id(mobile)}')Different Variable of Same Value You can create two lists with the same values using different variables. Here’s an example:

# Creating two lists with the same values

list1 = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

list2 = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

# Checking if they have the same values

print("Are the lists equal?", list1 == list2)

# Checking if they are different objects (different variables)

print("Are the variables different?", list1 is not list2)

# Checking memory address of both

print(id(list1),id(list2))

print(id(list1) == id(list2))In this example, list1 and list2 have the same values, but they are different objects with different memory addresses. The == operator checks for equality of values, and the is operator checks if they refer to the same object in memory.

4.19 copy() and deepcopy() functions

The copy() and deepcopy() functions are used to create copies of objects in Python, but they behave differently when dealing with nested or complex objects like lists within lists or dictionaries within dictionaries.

Here’s an example using both functions:

import copy

# Original list with nested lists

original_list = [1, [2, 3, 4], 5]

# Using copy() to create a shallow copy

shallow_copy = copy.copy(original_list)

# Using deepcopy() to create a deep copy

deep_copy = copy.deepcopy(original_list)

# Modifying the original list

original_list[1][0] = 'X'

# Displaying the original and copied lists

print("Original List:", original_list)

print("Shallow Copy:", shallow_copy)

print("Deep Copy:", deep_copy)

# Output :

# Original List: [1, ['X', 3, 4], 5]

# Shallow Copy: [1, ['X', 3, 4], 5]

# Deep Copy: [1, [2, 3, 4], 5]In this example, copy.copy() creates a shallow copy, and copy.deepcopy() creates a deep copy. The difference becomes apparent when the original list is modified. The shallow copy retains references to the nested lists, so changes inside the nested lists are reflected in both the original and shallow copy. The deep copy, on the other hand, creates entirely new objects for the nested lists, making it independent of changes in the original.

4.20 Practice Questions

How would you assign the value ‘world’ as the third element in a list stored in a variable named eggs? (Assume eggs contains [1, 3, 5, 7, 9]).

eggs = [1, 3, 5, 7, 9]

eggs.insert(2, ‘world’)

print(eggs)

my_list = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50]

How would you remove the element 30 from the list without using the remove() method?

my_list = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50]

new_list = [i for i in my_list if i != 30]

print(new_list)

numbers = [3, 1, 4, 1, 5, 9, 2, 6, 5, 3, 5]

How can you remove all occurrences of the number 5 from the list without using the remove() method?

numbers = [3, 1, 4, 1, 5, 9, 2, 6, 5, 3, 5]

new_numbers = [num for num in numbers if num != 5]

print(new_numbers)